by Erica DeVoe

The past three books I’ve read changed me. Actually, they defined me. No wait, they articulated what I’ve always known myself to be, but I had yet to articulate it for myself… and that, that is what saved me.

Grant Lichtman’s The Falconer, Warren Berger’s A More Beautiful Question, and Santana and Rothstein’s Make Just One Change (MJOC) have brought me off that ledge of not knowing how to exist as a 21st century educator within a 19th century framework, mindset, and bureaucracy. Everything I have been saying as an educator for the past 6 or so years was not backed by strong, or something even tangible, actions and outcomes. I want my students to think for themselves, to ask questions Google can’t answer, to “be engaged” (but what does that really mean and look like?), to look at the world critically yet compassionately. These authors illustrate and inspire the strategies for doing, instead of just saying or hoping. DOING is going to be what sets 21st century educators, institutions, administrations, and students apart from their 19th and 20th century counterparts. And the easiest strategy to start the DOING is RQI’s Question Formulation Technique.

I read MJOC last weekend, literally. So this past week, I began thinking of how I could best integrate the QFT into my already-conceived vision of what this third quarter of the school year would look like for my students. I teach two distinctly different groups of students – one is a group of 9 behaviorally challenging and below grade-level students.

It went like this: I set up an online poll with the prompt “What do you want to learn about this semester?” That went south when several expletives appeared on the screen. Onto Plan B. I passed out a sheet of blank paper and said “Write one thing down that you want to know more about – anything.” And they did it. Progress. I wrote down “School Violence” on the board as my topic (I knew they would be intrigued by that as opposed to something like “Metacognition in Learning”). Then I presented The Rules and we collaboratively asked questions about my topic. In about 7 minutes, we had 20 questions. Now they were to do it individually. And they did it. Progress. We then shared our questions and I was blown away at their efforts and honesty. Their level of engagement in the activity and each other’s ideas was not only exhilarating, but literally heart-warming.

I explained to them how those questions were going to lead them to a four-artifact standards-based portfolio that represents their learning over the semester. They will be evaluating and critiquing a TED Talk for its rhetorical effectiveness, composing a research paper, reading a piece of fiction related to or illustrating their topic, and writing a reflective essay about the entire semester’s learning process. These four artifacts each will answer different questions that they “question-stormed” through the QFT, thus giving them a multi-dimensional and multi-genre view of a topic of their choice. But beyond that, I truly believe this might be the start of them finding themselves as learners and citizens, if not quite citizens of the big bad world just yet, at least citizens within the community of Westerly High School. Maybe this will bring them off that precipice they so adeptly, yet frustratingly, dance on.

“Their level of engagement in the activity and each other’s ideas was not only exhilarating, but literally heart-warming.”

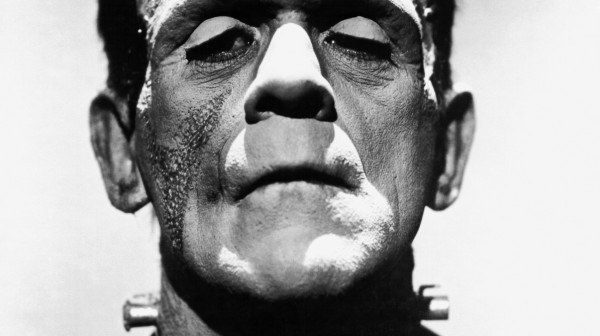

My second group of students is 26 heterogeneously grouped 12th graders in a course called Modern Topics (which is only two years old, so there are no deeply consecrated “traditions” binding us, as teachers). We just started reading Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein and as a summative assessment each student builds a website with curated materials representing a modern topic they have tied to the novel (many choose abnormal psychology or stem cell research/cloning topics). Since the New Year, I have been racking my brain trying to figure out how to get better products out of the students. I can’t spend another year telling myself, “I designed something worthy, they’re just apathetic.” And like a beacon shining through a dark foggy night guiding me away from that precipice of blame, the QFT “appeared” to me and inspired a shift in approaching the reading.

We read the Letters and first four chapters of Frankenstein. I gave each group (3-4 kids) a word (Loss, Family, Ambition, Learning, Victor, Storytelling, Science) and had them just contextualize that word with details from the novel. This took 2-3 minutes. Then I presented The Rules and they were off. They were very hesitant to ask questions “beyond” the novel though I didn’t violate Rule #2 (Don’t stop to discuss, judge, or answer) while they were asking. Once their pace slowed, I gave them each two highlighters – yellow is for the questions that can be answered by reading some more (“closed” within the book), green is for questions that would require looking beyond the book (“open” to the world). Then I had them revise all their “closed” questions to “open” questions. Questions such as “Why did Victor love science?” became “Why do people love science?” and so on. And then we shared… and it was magical.

We read the Letters and first four chapters of Frankenstein. I gave each group (3-4 kids) a word (Loss, Family, Ambition, Learning, Victor, Storytelling, Science) and had them just contextualize that word with details from the novel. This took 2-3 minutes. Then I presented The Rules and they were off. They were very hesitant to ask questions “beyond” the novel though I didn’t violate Rule #2 (Don’t stop to discuss, judge, or answer) while they were asking. Once their pace slowed, I gave them each two highlighters – yellow is for the questions that can be answered by reading some more (“closed” within the book), green is for questions that would require looking beyond the book (“open” to the world). Then I had them revise all their “closed” questions to “open” questions. Questions such as “Why did Victor love science?” became “Why do people love science?” and so on. And then we shared… and it was magical.

“I will be able to … proudly say my students did it… themselves.”

Each group read aloud all their questions and the other groups had a chance to add to the topic’s “bank” of questions. As I was listening to the questions, my mind was reeling with next steps. First, they are going to each pick their “priority questions” for our Socratic Seminar discussing Part I of the novel. We are then going to continue questioning and categorize all the questions into topical lenses through which to read the rest of the novel. Whatever lens they choose to read through, those questions are their guides. Those questions are what will drive their digital collections. And hopefully, in about 4 weeks, I will be able to officially step back from the ledge of blame and proudly say my students did it… themselves. Who knows, maybe in 4 weeks, they will look at their work and claim that assignment, or even the course itself, brought them off the ledge of boredom, disengagement, and apathy.

The book’s concepts live up to its title. Making one small change can shift your instruction and a student’s experience. Making one small change can help refine an assessment. Making one small change can bring you back from the recesses of frustration or blame. Most importantly, making one small change can instill confidence and efficacy, and lead our students toward pride, ownership, and independence… and I don’t know a single educator who doesn’t have those hopes for their students.

Erica DeVoe is in her tenth year teaching English Language Arts at Westerly High School, a suburban public high school in Southern Rhode Island serving just under 1,000 9-12 grade students. She recently earned her National Board Certification in 2013 and has been the English Department Chairperson for the past three years. You can follow her on Twitter @Mrs_DeVoe or her blog “What’s Important?” www.ericadevoe.wordpress.com

Erica DeVoe is in her tenth year teaching English Language Arts at Westerly High School, a suburban public high school in Southern Rhode Island serving just under 1,000 9-12 grade students. She recently earned her National Board Certification in 2013 and has been the English Department Chairperson for the past three years. You can follow her on Twitter @Mrs_DeVoe or her blog “What’s Important?” www.ericadevoe.wordpress.com

I feel this resource is going to be invaluable in generating cognitive rigor. For many years , most teachers have crafted the task of presenting information, however this is only 10-15 % of the instructional process. According to one of the most recent shifts in education( Common Core State Standards) , teacher must learn to shift from presenter to facilitator. This change allows students to ponder and digest the information placed before them with their peers and to be more actively involved in learning . If students are allowed to meditate, they will be able to respond effectively to content subjects and make connections. Questions serve as the media by which effective reflections can be generated by both teachers and students.

Thank you so much for this resource.

S. Jennings, Literacy Coach